Food For Thought: Can Your Diet Influence Your Dreams?

- neuwritephl

- Jan 2, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Jan 2, 2025

By: Abneil Alicea Pauneto

December 2024

Ever woken up from a wild dream and wondered if that late-night cheese and crackers was to blame? The notion that food influences our dreams is a long-held belief. While it feels plausible, the scientific evidence is surprisingly complex. The connection between diet and dreams remains a fascinating scientific mystery. Yet, combining the small body of research with what we know about the brain’s activity during sleep opens the door to some intriguing possibilities.

First, what are dreams? The field broadly defines them as conscious experiences during sleep, occurring across two main stages: rapid eye movement (REM) and non-rapid eye movement (NREM) (1). While dreams were once thought to be exclusive to REM sleep, modern research reveals that they can occur throughout the night, differing in content depending on the sleep stage.

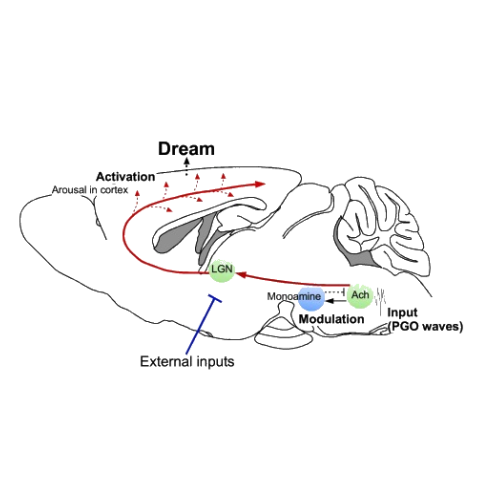

Theories about dream generation have evolved over time. The two most recent models— the activation-synthesis model and the dopaminergic forebrain mechanism— offer insight into how the brain creates dreams. The activation-synthesis model describes how, during REM sleep, the brainstem, a region at the base of your brain, sends signals that activate other brain areas like the visual cortex and thalamus, generating internal inputs. These inputs— made up of sensory, emotional, and conceptual information from memories and thoughts— are then synthesized to create dreams (2,3).

On the other hand, the dopaminergic forebrain mechanism highlights the role of dopamine, a key brain chemical, in dream generation. Research shows that stimulating the forebrain can trigger dreams during REM and NREM sleep. At the same time, damage to this area can eliminate dreams entirely. Additionally, drugs that affect dopamine levels have been found to influence dream content. This model also emphasizes the involvement of the brain’s reward system, known as the mesocortical-mesolimbic system, linked to emotions, motivation, and exploratory behavior. This connection suggests that dreams may reflect deeper emotional and motivational processes, making them more than just random mental activity (3,4).

Okay, back to the snacks. Can what you eat influence your dreams? The short answer: maybe. The longer answer: there’s not much research, but what we do know is intriguing. While science hasn’t confirmed a direct link, many believe their diet affects their dreams. For example, correlational research suggests that those who prefer organic foods report more frequent and meaningful dreams, often with recurring themes like flying or water. In contrast, fast food consumers have fewer and less vivid dreams. Surveys on late-night eating habits further support this idea, with nearly 18% of participants believing specific foods influence their dreams (5). Dairy products are often cited as culprits for vivid or disturbing experiences (6). A 1968 study explored this connection further by examining the impact of hunger, thirst, and sensory input on dreams. Participants deprived of food and drink before a spicy meal and exposed to audio cues about a refreshing drink during sleep experienced an increase in drink-related dreams, with those who dreamt of quenching their thirst actually drinking less water upon waking (6, 7, 8). These diverse findings suggest a complex interplay between diet, sensory input, and our sleeping minds.

Even though research is limited, and neuroscientists have not yet identified a direct link between food and dreams, additional evidence makes this connection plausible. First, our brains don’t shut off entirely during sleep; instead, sensory processing continues, allowing external stimuli to shape dream content (9). Exposure to specific odors during sleep has been shown to evoke related dream themes, linking sensory input to dream experiences (10,11). Your diet also significantly influences neuromodulators, such as serotonin, which regulates various brain circuits and impacts mood, sleep quality, and dream patterns (12). Serotonin is a key component of the gut-brain axis— a bidirectional communication network linking the gastrointestinal tract and brain. Through this interconnected system, dietary choices can influence brain activity, with biochemical signals from the gut potentially shaping dream content and overall mental states (13). So, it is possible that consuming foods like meat and dairy, which can elevate serotonin levels, could increase your brain activity, ultimately influencing your dream content.

Our limited view of the connection between food and dreams stems from the significant challenges researchers face when studying dreams. One major difficulty is that the neural processes responsible for REM sleep overlap with those that generate dreams, making it hard to separate the two. Additionally, dreams occur during both REM and NREM sleep, with each stage producing distinct types of content and characteristics, further complicating the research (3). Studies are also hindered by the reliance on individuals recalling their dreams after waking (14)— can you recall what you dreamt about last night? Chances are that many of you can’t remember or that it is difficult for you to remember. This process is prone to memory distortion, forgetting, or reconstruction (1, 15, 16, 17). Furthermore, research that relies on surveying dreams is often correlational and fails to account for confounding factors that may influence dream content. These challenges underscore the need for innovative methods to better understand the intricate relationship between sleep, dreams, and external influences such as diet.

Advances in neuroimaging and even machine learning could help scientists pinpoint how specific foods or nutrients influence the brain during sleep (1). Imagine one day being able to engineer your dreams by tweaking your diet or using dream-targeting tools like sensory stimulation. For now, though, the evidence is more anecdotal than scientific. But that’s okay— dreams are supposed to be mysterious, right? So, the next time you wake up from a vivid dream, feel free to blame (or thank) that midnight snack, even if its relationship with your dreams is not backed by science yet. Whether it’s food, memories, emotions, or a combination of these shaping your nighttime adventures, one thing’s for sure. There’s still a lot to learn about in the dream realm.

References:

Mallett, R., Konkoly, K. R., Nielsen, T., Carr, M., & Paller, K. A. (2024). New strategies for the cognitive science of dreaming. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 28(12), 1105–1117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2024.10.004

Hobson, J. A., & McCarley, R. W. (1977). The brain as a dream state generator: An activation-synthesis hypothesis of the dream process. American Journal of Psychiatry, 134(12), 1335–1348. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.134.12.1335

Tsunematsu, T. (2023). What are the neural mechanisms and physiological functions of dreams? Neuroscience Research, 189, 54–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neures.2022.12.017

Solms, M. (2000). Dreaming and REM sleep are controlled by different brain mechanisms. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 23(6), 843–850. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X00003988

Kroth, J., Briggs, A., Cummings, M., Rodriguez, G., & Martin, E. (2007). Retrospective reports of dream characteristics and preferences for organic vs. junk foods. Psychological Reports, 101(1), 335–338. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.101.1.335-338

Nielsen, T., & Powell, R. A. (2015). Dreams of the Rarebit Fiend: Food and diet as instigators of bizarre and disturbing dreams. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, Article 47. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00047

Dement, W., & Wolpert, E. (1958). The relationship of eye movements, body motility, and external stimuli to dream content. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 55(6), 543–553. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0040031

Bokert, E. (1968). The effects of thirst and a related verbal stimulus on dream reports (Doctoral dissertation). New York University.

Andrillon, T., & Kouider, S. (2020). The vigilant sleeper: Neural mechanisms of sensory (de)coupling during sleep. Current Opinion in Physiology, 15, 47–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cophys.2019.12.001

Schredl, M., Atanasova, D., Hörmann, K., Maurer, J. T., Hummel, T., & Stuck, B. A. (2009). Information processing during sleep: The effect of olfactory stimuli on dream content and dream emotions. Journal of Sleep Research, 18(3), 285–290. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2869.2009.00737.x

Schredl, M., Hoffmann, L., Sommer, J. U., & Stuck, B. A. (2014). Olfactory stimulation during sleep can reactivate odor-associated images. Chemosensory Perception, 7(3-4), 140–146. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12078-014-9175-1

Peuhkuri, K., Sihvola, N., & Korpela, R. (2012). Diet promotes sleep duration and quality. Nutrition Research, 32(5), 309–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nutres.2012.03.009

O’Mahony, S. M., Clarke, G., Borre, Y. E., Dinan, T. G., & Cryan, J. F. (2015). Serotonin, tryptophan metabolism and the brain-gut-microbiome axis. Behavioural Brain Research, 277, 32–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2014.07.027

Dennett, D. C. (1976). Are dreams experiences? The Philosophical Review, 85(2), 151–171. https://doi.org/10.2307/2183854

Schacter, D. L. (2022). The seven sins of memory: An update. Memory, 30(1), 37–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2021.1898760

Rosen, M. G. (2013). What I make up when I wake up: Anti-experience views and narrative fabrication of dreams. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, Article 514. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00514

Nemeth, G. (2023). The route to recall a dream: Theoretical considerations and methodological implications. Psychological Research, 87(4), 964–987. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-022-01695-3

Comments